George Hoberg

February 13, 2012

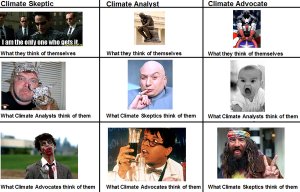

There are three competing logics of climate politics. One is the climate skeptic, convinced either that climate science is exaggerated or that the costs of action outweigh the benefits. Another is the climate policy analyst who accepts the climate science and evaluates policies designed to meet climate targets based on their cost-effectiveness. The third is the climate advocate, who is convinced there is a climate crisis and focuses on which political strategies are best suited to decarbonizing the energy system. While having little patience for climate skeptics, the analyst also bridles at the open advocacy of climate advocates, scoffing at their exaggerated rhetoric and bemoaning the inefficiency of their prescriptions. In doing so, however, they frequently misunderstand the logic of politics guiding the advocates.

The Climate Skeptic

I have a hard time understanding the logic of climate skepticism from serious people. I get that some are contrarian by nature and revel in railing against orthodoxy of any sort. I get that there are widely divergent views of the appropriate relation between the government and markets, and that serious climate policy might seem alarming to those with a libertarian bent. But I have a very hard time understanding how any conservative who understands welfare economics can deny that there are certain well understood conditions, particularly externalities and public goods, which justify a strong government role in climate policy. I find it particularly hard to understand what appears to be a willful inability to accept the logic of probabilities implied by the best climate science. Even though it is frighteningly cynical, I find it easier to understand Doonesbury’s character depicted as “the honest man,” who accepts the science but opposes sound climate policy “because I care much more about my short-term economic interests than the future of the planet! Hello?”

The Climate Policy Analyst

But this post is not about the logic of climate skepticism, which is too mysterious. I want to focus on the difference in the logics of climate advocates and climate policy analysts. The conflict in perspectives between these two views was reinforced in my mind again Saturday by a New York Times column by Joe Nocera about the KeystoneXL pipeline. The column accuses climate advocates of exaggerating the significance of KeystoneXL’s contribution to global warming. “The crude oil from the tar sands of Alberta, which the pipeline would transport to American refineries on the Gulf Coast, simply will not bring about global warming apocalypse.” Therefore, Nocera’s logic seems to go, given that we need the oil and Canada is a reliable partner, the pipeline should be approved.

Several leading climate policy analyst/bloggers/tweeters chimed in “yup, that’s what we’ve been saying for months.” Andrew Revkin, the dean of climate blogging at the New York Times, tweeted a reference to his September 2011 overview piece that generally supports Nocera’s conclusion. Revkin’s piece refers to the affirming work of two other leading climate policy analysts, Andrew Leach at the University of Alberta and Michael Levi at the Council of Foreign Relations. The analysts’ essential argument is two-fold. First, given the amount of GHG emissions enabled by the pipeline and the nature of North American and especially global oil markets, the marginal impact of the KeystoneXL pipeline on global GHGs will be insignificant. Second, there are much more cost-effective ways to reduce GHG emissions than blocking pipelines.

I believe that both are these arguments are unquestionably correct. But I also believe that they completely miss the point about why environmentalists are so opposed to the KeystoneXL. The logics of analysis and advocacy are fundamentally different. The analyst is guided by aspirations for truth and well-reasoned argument, and guided largely by the value of maximizing the cost-effectiveness of solutions. They chaff against exaggerations and misuse of data by advocates on all sides, and search for the best reasoned argument for the most efficient path forward.

The Climate Advocate

In contrast, the climate advocate is trying to maximize political leverage in an effort to foster systemic transformation of the energy system. The logic of political action and movement building is different from the logic of policy efficiency. The advocate works to strategically frame problems and solutions that work politically, not those that best adhere to the standards of analytical rigor. Frequently, this involves exaggerated claims that aggravate the analyst.

Probably the best example from the KeystoneXL is the James Hansen claim that the pipeline represents a “carbon bomb” because it increases access to Canada’s unconventional oil deposits in the tar sands. [Correction: the phrase attributed to Hansen and reported repeatedly by McKibben and others is "fuse to the biggest carbon bomb on the planet."] If fully exploited, Hansen claimed, the tar sands could add 200 ppm of GHGs to the atmosphere, meaning it’s “essentially game over” in the battle against climate change. This” game over” frame was repeated again and again by Bill McKibben, the lead organizer of the anti-Keystone. Analysts chastised him for exaggeration and confusing the magnitudes at stake. Turns out Hansen and McKibben have a pretty good understanding of the magnitudes of carbon flows. It’s just they find the metaphor of “carbon bomb” and “game over” enormously powerful as a catalyst for mobilizing people, so they continue to use it.

McKibben and his allies didn’t choose to draw a line in the sand on KeystoneXL because it was the most cost-effective policy to reduce GHG emissions. They picked it because it made political sense given the state of the climate movement in US and global politics. Having failed so spectacularly at Copenhagen and then in the US Congress to get meaningful action, McKibben and Co. recognized that to have meaningful success, more direct action would be required to galvanize the intensity of preferences at the grassroots level needed to foster a powerful social movement. Keystone XL turned out to be a perfect short-term vehicle for that. It was a point of leverage they could use to focus concentrated pressure, and it turned out to be a spectacular success on its own terms.

The Leap of Faith

I’ve felt the conflict between these two logics very personally. As an academic, I’ve always prided myself on the commitment to analytical reason and been uncomfortable with the rhetoric of advocates even when I’ve shared their values. But in recent years I’ve felt increasingly unsettled in that stance as the gravity of the climate crisis has become more apparent. The past two decades of climate politics have clearly demonstrated that “speaking truth to power” has not been effective at inspiring climate action. And as I’ve tried to come to a deeper understanding about humanity’s failure to act yet on climate change, I came to an insight that transformed my stance.

When you consider the structure of the climate challenge as a public goods and public choice dilemma, you can see that if we are guided by short term material thinking we will simply be incapable of rising to the challenge of taking the concerted action sufficient to avoid dangerous climate change. The logic of the climate policy analyst is dominated by this economic rationality that can’t generate the necessary solutions. To envision a capacity to act you need to take a leap of faith that enough citizens and leaders are willing to act on moral, not economic grounds. You take climate action not because it is in your or your nation’s interests, but because it is the right thing to do. And you need to start acting that way yourself.

From Analyst to Advocate

UBC was fortunate to have Bill McKibben come visit and give a series of talks in November. I had breakfast with him in a small group and challenged him on all of these factual issues. What was immediately apparent is that he understood all of the criticisms, but was simply working from a different logic about how to maximize political opportunities. In a larger group he had a session about the tensions between academics and advocates. He bemoaned analysts who were “in love with the caveat” and unwilling to join hands with advocates in the fight for climate action. He explained that he was sensitive to the concerns of many academics that they would be sacrificing their credibility if they engaged in advocacy. He then spoke of the gravity of the climate crisis, calling it the “greatest challenge of our time,” and asked: “What are you saving your credibility for?”

McKibben closed his November speech at UBC with the following words:

“There’s no guarantee we’ll win the fight against climate change. There are scientists who think we’ve waited too long to get started in this fight, and there is too much momentum behind this heating. There are political scientists who think the odds are simply too high; there’s too much money piled on the other side. If you were a betting person you might be wise to bet with them because we’ve been losing more or less for twenty years. But that is not a bet you are allowed to make. The only stance for a moral human being when the worst thing on earth is happening is to get up in the morning and figure out how you can change those odds.”

What I’m doing is working with students at UBC to create a campus climate movement, UBCC350, oriented towards fostering meaningful government action against carbon exports from British Columbia. By taking on a more explicit advocacy role, I’m not abandoning the commitment to analytic rigor typified by the logic of the analyst. I see myself as harnessing that in the service of advocacy.

Up next: more on the model will are building for using university campuses as strategic nodes in the climate movement.

That is definitely a helpful explanation of why analysts and advocates each keep thinking “What is wrong with those guys?”

An illustration might be Jen Gerson’s article, which is good and balanced, except it still rests on the assumption that “how our society operates” is going to be able to continue without changing.

http://www.calgaryherald.com/news/Northern+Gateway+pipeline+proposal+draws+into+quagmire+conflict/6140300/story.html

It is not correct to say that all “analysts” who accept climate science (broadly speaking) also approve individual pipeline projects, or at least claim that blocking them is not justified on grounds of mitigating AGW.

Much depends on the scope of the analysis. For example, Marc Jaccard has demonstrated that current plans for rapid expansion of the oil sands is incompatible with meeting Canada’s stated 2050 target (65% reduction in GHG emissions from 2005 levels). His conclusion? Long-term infrastructure decisions should be guided by their impact in the *long-term*, which implies that pipeline expansion should not be approved. He also points to research that shows that the market for oil sands bitumen would not be viable, if an effective global price for carbon were established. And *any* plausible path, say, to 450 CO2e ppm will curtail oil sands expansion greatly.

See:

http://deepclimate.org/2012/01/26/mark-jaccard-calls-out-stephen-harper-on-oil-sands/

Far-sighted analysts who examine the issues in the context of the next few decades, as well as the implications of *all* infrastructure, will come necessarily to different conclusions than ones who focus on a single project at a time over the next 10-20 years.

I understand and sympathize with your dilemma. But it would be a mistake to yield the “analyisis” point of view to pipeline proponents. Given the proper terms of reference, the analytic and activist view are better aligned than pipeline proponents would have you believe.

Excellent post.

I think having analysts chaffing at the exaggerated claims of the advocate is vital in advancing the goals of advocates themselves. In this way, the logic of the analyst is not competing with that of the advocate, but complementary.

As you discussed, the advocate, trying to maximize political leverage, is a powerful force through their frequent appeal to emotionally charged and exaggerated language. A downside of these types of arguments for action is that they can undermine understanding and respect for the underlying science driving the need for action.

As a result, the emotionally based arguments of the advocate may have helped give rise to the unreasonable climate skeptic. It is easier for skeptics to dismiss climate science when advocates use exaggerated and emotionally charged language, than if their claims were carefully cited or the analyst was in control of the megaphone at the protest rally. To the advocates credit, there’d probably also be a lot less awareness of the problem.

There is an important role here for analysts, especially when Bill McKibben says, What are you saving your credibility for?

By resisting the excesses of the advocates’ claims, while still supporting many of their goals, analysts maintain credibility for the science and reasoning on which advocates ultimately rely. Analysts help buttress the fundamental arguments that advocates use, preventing an undermining of the respect for science and academia that will remain key for understanding and responding to complex problems such as climate change.

Without the analyst, the next battle pitting solid science vs. entrenched positions and interests will be that much harder to win.

Chris Rose (who has helped plan a lot of campaigns) argues that if politics is the art of the possible, then campaigns (what advocates do) are about shifting the terrain such that new outcomes become possible.

He makes a useful distinction between educating (which is about discovering and exploring complexity, including a solid understanding of power and the various shades of grey) and campaigning (which is about using that analysis to focus in on motivating people to take a particular, strategic action). The trick is to identify the action which you can motivate people to take and which will shift power relationships such that achieving your long-term goal becomes more “possible”.

Short version here: http://www.campaignstrategy.org/twelve_guidelines.php?pg=intro

A few years ago, I blogged about the dilemma I faced: should I be a rigorous academic/policy analyst or should I be a passionate and ardent activist?. The model you have proposed here, Bill McKibben’s talk, and my countless conversations with you and with other senior scholars who have successfully embraced activism while not forgetting the importance of rigorous scholarship and paying attention to the weight of evidence gives me hope that I can strike that balance. Right now I find myself more on the side of the policy analyst than the activist, but as you propose, these aren’t mutually exclusive (and shouldn’t be, there is a role for each).

Some very interesting insights and observations. Thank you. A couple of my own:

- the ‘Honest man’ is also an old man, with nothing more than short-term interests to look forward to at a personal level. Climate change isn’t going to affect him.

- Putting aside questions of whether Keystone really would mean ‘game over’ (it wouldn’t, but its friends would), the tenacity with which the Keystone pipeline is being pushed demonstrates what happens when a line in the sand is drawn. On evidence to date, it seems to have been drawn in the right spot.

Pingback: Hold Strong to Authenticity – The Three Logics of Climate Politics | Unintended Consequences Documentary Project

I have posted my response to your excellent piece on my blog found here. http://intentionalfilm.wordpress.com/2012/02/14/hold-strong-to-authenticity-the-three-logics-of-climate-politics/

As a climate activist it is so frustrating that it is the climate analysts that get the ink and they use it to undermine our work. They need to get on side. The only way we have anything that looks like a good outcome on climate is by speeding up the “oh shit” moments people have when they “get it” because politically there is no will to do what is required. We need to face that fact that facts are not whats holding this up- people who muddy the waters are.

“Second, there are much more cost-effective ways to reduce GHG emissions than blocking pipelines.”

This probably isn’t true in Canada today. Under this government, blocking pipelines seems to be just about the only useful thing people concerned about climate change can do.

Pingback: Climate Advocates and Climate Activists Are Butting Heads Over the Keystone XL Pipeline | Ecocentric | TIME.com

Pingback: Pipeline Politics: Keystone, Advocates and Analysts | Wildrose Meadowlark Constituency Association

Thanks for this thoughtful post, and for the work you are doing with the UBC students re: climate.

You might want to consider linking forces with Citizens Climate Lobby, a nonpartisan group that is focused on creating the political will for a sustainable climate, and on empowering individuals to exercise their own political power. We in the climate movement can’t afford to keep reinventing the wheel and working in isolation.

Here’s the website, fyi – http://citizensclimatelobby.org/

Good post. There is a fourth logic: it’s the “change isn’t going to happen on its own, so I’m getting my hands dirty” approach. This fourth type of person, the type who gets directly involved in projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, is often frustrated by all the other types. The skeptic certainly isn’t doing it; the analyst is probably working too hard for too little money to have any spare time for hands-on work; and only a minority of advocates have the skills, aptitude, or interest in getting their hands dirty. Furthermore, both the analyst and the advocate think their work will get the job done. As such, not enough is happening. So the fourth types continue to struggle without the mass action (by action, I mean working with physical tools and such) required to turn this ship around. The revolution will not be a policy brief.

Pingback: Climate analysts are from Mars, climate activists are from Venus … but they both live on Earth | Grist

The main reason for lack of political action is the reasoning expressed in the Byrd-Hagel resolution.

If it was an issue the politicians took seriously, the solution would be a worldwide independent push for nuclear power. But instead, international negotiations get hung up on how the developing world is not required to take any action, and how much the richer counties are to pay the poorer ones. If you was cynical, you might suspect that was the main point. Byrd-Hagel: it’s been the policy of every US government since ’97, left or right.

Climate sceptics are easy to understand. They’re the ones who think comments like “Why should I make the data available to you, when your aim is to try and find something wrong with it?” aren’t very scientific. Neither is “What the hell is

supposed to happen here? Oh yeah – there is no ‘supposed’, I can make it up. So I have.” Others disagree, of course, and I do understand why, but beyond that we get into complicated technical arguments for which most people have to trust the experts. They simply disagree on which people are really experts.

The serious scientist’s case, short and simple:

http://jonova.s3.amazonaws.com/guest/evans-david/skeptics-case.pdf

That should help with: “I have a hard time understanding the logic of climate skepticism from serious people.”

” I have a hard time understanding the logic of climate skepticism from serious people. ”

Many serious people have looked into the science of climate change and found it to be very weak. It is not to do with ‘reveling in railing’ or with being ‘libertarian’ or ‘conservative’ and there is nothing ‘mysterious’ about it at all.

If you seriously wish to understand the logic, read David Evans (if his link doesn’t work you can find it on google). Read Steve McIntyre’s Climate Audit blog (though it took me a year of hard work to understand the issues). Read The Hockey Stick Illusion. Read the climategate emails.

You should also be aware that one of the reasons for the growth of skepticism is the tendency of some academics to start behaving like political activists.

About David Evans:

http://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php?title=David_Evans_(Australian_skeptic)

http://www.desmogblog.com/who-is-rocket-scientist-david-evans

http://scienceblogs.com/deltoid/2008/07/the_australians_war_on_science_16.php

1) I second the comments of Deep Climate.

2) You quote Hansen as claiming that the pipeline represents a “carbon bomb”. Not so small problem: the link from your quote does not contain the phrase. Now, a quick search confirms that Hansen has called the pipeline the *fuse* to a large carbon bomb. Conclusion: you distorted Hansen’s words to fit your exaggerated distinction between analysts and advocates, whereas Hansen’s actual metaphor is more thoughtful than you give him credit for, and deftly combines the analytic and activist sides you are at pains to separate.

“What are you saving your credibility for?”

That’s a disappointing idea. It acknowledges that empirical rigor can be sacrificed for advocate ends. And further, it suggests that such a trade is necessary to achieve those advocate ends. Is climate science, cold, stoic, and without a bit of advocacy, actually insufficient to reach those ends? Said another way, doesn’t that mean that the advocate is exceeding the empirically-based truth?

I have a problem when people exceed empirically-based truth. The reason I am motivated to do climate policy is because I recognize that the empirically-based evidence compels action. The action is only justified because it is empirically based. If empirical evidence has no meaning–if it can be exceeded or discarded because we want to–we should have a toast for the last four centuries of mistaken belief. Maybe we could do it on a nice beach and watch the sea rise as we helplessly accept our fate, having thrown away the only tools we have to stop it.

Its like tearing off a ship’s rudder to hoist it like a sail. Cool, you’re moving faster now, but just adrift, subject to the whims of the wind. Empiricism says you must have the rudder at all times, even if it slows you down, because ultimately that steering is the only thing letting you control your direction, i.e., keeping you from being a climate skeptic. Remember why you got in the climate ship in the first place (empirical evidence), and ask whether you would have bothered if you knew it was just one of many rudderless ships adrift at sea, indistinguishable its submission to arbitrary local winds.

Now, no one suggests that we tear off the whole rudder, or abandon all pretense of empirical thought. George Hoberg and Bill McKibben just suggesting it’s okay to exceed the empirical evidence from time to time. But where do you draw the line? That’s not a rhetorical question, I genuinely don’t know. I recognize that you probably _can_ exceed the evidence to spur people into action without wholesale setting yourself adrift. I just wonder how you can do so safely. How do you leash yourself to a foundation of empirical rationality while allowing any deliberate (as opposed to the inherent subjectivity scientists strive to minimize) deviation from it, even for a bit? How can you be sure 10 years from now you won’t find yourself astonishingly far from that empirical foundation, similar to the the inscrutable, fact-choosing skeptic you battle today?

Did any anyone get in the boat because he or she heard a report that they knew wasn’t based on empirical evidence? I’d wager no. No one is persuaded by the purposeful fact choosing of another, at least insofar as they are educated. So we all understand that we wouldn’t be climate advocates, analysts, or skeptics if we did not feel there was a rational/empirical basis for our position. No one is satisfied with just making stuff up and believing in it. So how can there be any leeway with presenting empirical evidence, which is fact choosing? Advocacy is fact choosing for another. I grant that given the amounts of empirical evidence and the difficulty in analyzing it there will always be a filter on information. Scientists will always have to make value choices but we should lament that, not celebrate it.

I think the empirical case for climate change is strong enough that we don’t need to sex it up. I understand the urge to do so, but know that credibility is what got us all here, and if we start trading it in for advocacy ends we lose the ability to discern truth–something more threatening to me than even climate change. What are you saving your credibility for? So that the next generation can discern truth as I have been able to.

Great comment by Morgan McDonald. I wholeheartedly believe his last line “The revolution will not be a policy brief.” More needs to be done; we all need to take more action. I did not interpret McKibben’s question “what are you saving your credibility for?” as Chris Chambers did. It is not a matter of sacrificing analytical rigor for advocate ends but rather being willing to stand up and take a side, being willing to get involved politically, but still speaking the truth. I don’t believe the advocate needs to exaggerate the claims or that all advocates do… generalization such as that are dangerous to make and defeat the ultimate purpose. If there was more cooperation, rather than animosity, between the analysts and the advocates we would be able to achieve far greater goals. Both analysts and advocates play an important role and neither should be diminished by the other but rather they should be seen as complimenting each other.

Pingback: Energy, Security, and Climate » The Death of Outdoor Hockey Has Been Greatly Exaggerated

Pingback: Mr Mulcair Goes to Edmonton, Giving Canadian Climate Hawks a New Dilemma | GreenPolicyProf

Pingback: Game over for Keystone KL: How environmentalists created Obama’s new climate test | GreenPolicyProf