George Hoberg

April 15, 2015

Last week, the prestigious Ecofiscal Commission released a report on climate policy that strongly advocated “The Way Forward” (its title) was through carbon pricing by the provinces. It is certainly no surprise that a group of economists would advocate carbon pricing. But it is quite striking that a group of economists would be so enthusiastic about provincial instead of federal leadership. Typically, economists advocate the most economically efficient solution, and a balkanized subnational process would seem inconsistent with that. Their endorsement of the provincial approach has been widely applauded in the media.

I have the utmost respect for both the member of the Ecofiscal Commission and the process they are using. However, before the idea of provincial leadership gains even more credibility (did we really just have a provincial “Climate Summit”), I did want to go on record that, in the opinion of this political scientist, it is a ridiculous idea. Only in Canada, and in particular in Harper’s Canada, could the outlandish notion that it is not the federal government’s place, indeed duty, to lead in developing a national climate policy gain such currency.

When George Grant published his famous essay in 1965, he was lamenting what he saw as Canada’s capitulation to American hegemony. In contemporary climate policy in Canada, we’re not capitulating to the US (which is racing ahead of us on climate). We’re capitulating to a self-imposed ideology of provincial paramountcy that blinds us the obvious merits of federal leadership.

The Ecofiscal approach contrasts with the recommendation of the Sustainable Canada Dialogues, a group of over 60 Canadian academics that released its report, Acting on Climate, last month. (I helped draft the section on climate policy instruments.) That report strongly endorsed national carbon pricing either through a national carbon tax or a national cap and trade system. The report states:

From a cost-effectiveness standpoint, a national GHG reduction plan has advantages. There would be concerns about fairness and competitiveness if emitters in one province paid a significantly different carbon price than emitters elsewhere in Canada. A cap and trade system would realize economic benefits from being applied to a larger and more diverse area.

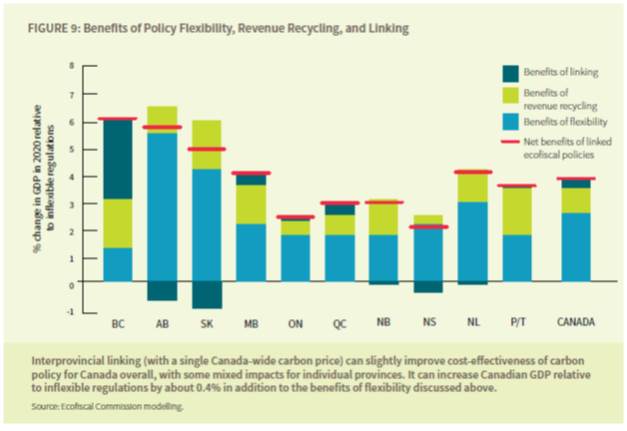

The Ecofiscal Commission report, however, was supported by much more extensive analysis, including elaborate modelling with a computable general equilibrium model that compared different scenarios. They compare the cost-effectiveness of provincial-led regulatory approaches, provincial-led carbon pricing approaches, and then linked (national) carbon pricing approaches. The most compelling conclusion of their report is that the modelling shows you get 89% of the gains from shifting from a regulatory approach to a more flexible carbon pricing approach at the provincial level. A national approach would be more cost-effective (getting you the final 11%), but the Commission uses the results to downplay the relative important of federal leadership and play up the huge gains available from provincial carbon pricing.

A more careful look at their results suggests that conclusion, in my view, is not justified, for three reasons.

The analysis overstates the cost-effectiveness advantage of a provincial approach: The figure below shows the relative benefits of three features: flexibility, revenue recycling, and linkage. The biggest gains in efficiency, 2/3rd nationwide, are from moving from a regulatory approach to a more flexible carbon pricing approach. An additional 24% comes from what they call revenue recycling, and the final 11% from linkage in a nationally-coordinated approach

The analysis is notable in how large the efficiency gain are by moving away from regulation, especially given the federal government’s continued reliance on that instrument. But I don’t think it is right for the Commission to attribute the gains from revenue recycling to a provincial-led approach. The Commission is certainly correct to note that the revenues collected from carbon pricing raise significant political questions about what to do with the revenues, a particularly sensitive topic in post-1980 Canada. Much of the tension can be addressed by returning any carbon pricing revenues to the province of origin. That can be done with a federal approach as easily as it can with a provincial approach. That’s what the Sustainable Canada Dialogues’ Acting on Climate report recommends (pp. 29-30). What the Ecofiscal Commission’s analysis models is not revenue recycling per se, but the economic impact of the income tax reductions made possible by a tax shift from income to carbon (as BC does with its revenue-neutral carbon tax). There’s no guarantee that provinces will use the revenues that way (Ontario is saying it won’t), and even if they did that’s not an impact reasonably attributed to a provincial-led approach.

There is indeed a substantial efficiency gain from moving to carbon pricing at the provincial level, but the degree of efficiency gains from a provincial vs. national approach are overstated.

The analysis relies on the dubious assumption that provinces will voluntarily meet their targets: The Ecofiscal Commission report builds its analysis on scenarios assuming provinces meet their existing targets. Doing this avoids two challenging features of a national approach: having a national discussion about sharing the burden for reductions, and mechanisms for compliance if provinces fail to meet their targets. First, you can also avoid a conflict over dividing up responsibility for a national target if you have a nationwide carbon tax or cap and trade program because, as the Sustainable Canada Dialogues report describes, “provincial emission levels would be responses to market signals, not established in advance” (p. 29).

Second, if there’s no strong federal leadership role, there’s no mechanism to force compliance with targets. Canada’s most stubborn climate challenge remains the reluctance of the country’s largest and fastest growing emitting province, Alberta, to enact sufficient climate policies to contribute to the national effort. (The Ecofiscal Commission notes that Alberta’s current approach “had no significant impact on annual GHG emissions or even emissions intensity” (p. 22).) BC and Saskatchewan will also face big challenges meeting their targets. We could surrender to a “naming and shaming” approach of voluntary provincial commitments, like the UNFCC is doing with international climate diplomacy. But that’s supposed to be the difference between nation-states and the international community. In nations, we have laws that we enact through the political process and that we agree to enforce.

Provincial leadership would produce large inequalities in burden-sharing: What the Ecofiscal report doesn’t say is how the carbon price varies across the country when provinces pick their own approach to meet their own target without federal coordination. Due to highly variable costs of control and stringency of targets across the provinces, their recommended approach would likely lead to widely different carbon prices across the country. This would create serious problems for competitiveness and fairness.

A national approach would be more cost-effective, coherent, enforceable, and equitable. If one or more provinces so strongly resisted adopting the national approach, it could work to exempt a province so long as mechanisms were put in place to ensure that the province contributed its fair share to the national reductions.

I completely get what the Ecofiscal Commission is trying to do, and applaud their sensitivity to political feasibility. We need to get going on climate policy, and in Harper’s Canada, provincial leadership offers the hope of quick progress. But don’t let the report raise doubts about the strong merits of federal leadership and a Canada-wide climate policy. It’s more efficient. It’s fairer. And it’s what nations do.