George Hoberg

September 21, 2015

A public policy is a purposive course of action or inaction by government. Understanding where policies come from requires an understanding of how the formal processes of government work. In Canada, these processes are a combination of rules written in the Constitution Acts and federal and provincial governments, but also unwritten “conventions” that have evolved over time from their origins in the traditions of parliamentary democracy in the United Kingdom and Canada. Canada is technically a constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary democracy. It is also a federal country, meaning that constitutional powers are divided between the federal government and the provinces. The governments at both levels consist of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. At the federal level, the legislature is made up of the elected House of Commons and the appointed Senate. The provincial governments are “unicameral”, meaning they don’t have a senate. (This post does not discuss either the Senate or the judicial branch.)

The Executive

The Queen is officially the head of state, but her work is delegated to her representatives in Canada: the Governor General at the federal level and Lieutenant Governors at the provincial level. Formal government actions – including legislation and regulations – require the approval of the Queen’s representatives. Approval or disapproval occurs with the “advice of the executive council”, the cabinet of the current government. By convention, this advice is always followed except in extraordinary circumstances.

The Prime Minister (or the premier at the provincial level) is the leader of the political party that holds the “confidence of the legislature”, meaning the support of a majority of the House (or the provincial legislature). That party, in particular its cabinet, forms “the government.” Ordinarily, this is the leader of the party with the most seats in the House of Commons (or provincial legislatures). When one party has a majority (as Harper’s Conservative Party has had from 2011 to present), who is Prime Minister is straightforward. It gets more complicated when no party wins a majority. It seems generally understood that the party that wins the most seats in an election gets the first opportunity to form a minority government. (They could also go into formal coalition with another party to form a majority.) Technically, the convention is that it’s up to the Queen’s representative, and it’s conceivable that the Prime Minister’s party could be given an opportunity to demonstrate they have the confidence of House even if they don’t win the most seats in the election.

The cabinet consists of individuals, selected by the Prime Minister usually from his or her own party in the legislature. Members of the cabinet are known as ministers, and are responsible for the management of one of the government’s major departments (e.g., Finance, Natural Resources, Environment). Deputy ministers are the senior public servant in each ministry. They are not elected, but appointed by the government to manage the ministry under the direction of the minister.

The prime minister and cabinet are executive officials, but they are also members of the elected legislature, creating a quite different arrangement from the one that exists in a separation of powers system like the United States, where members of the executive branch are prohibited from being in the legislature.

Legislatures in an Executive-Centred Parliamentary System

Despite being referred to as a parliamentary democracy, legislatures play surprisingly little direct role in modern Canadian governance. The executive-centred form of government results from the relationship between the prime minister (or premier) and the members of their party in the legislature. Members of the legislature are divided into party caucuses, which decide the party’s positions on votes that come up in the legislature. The government’s party has a caucus, and other parties represented in the legislature also have a caucus, the most important of which is the official opposition – the party outside the government that has the most seats in the legislature.

In practice, party members almost always vote in accordance with their party’s policies, known as “party discipline”, for several reasons. Members of the government party want to ensure their party continues in that role, so they need to work together to ensure their party maintains the confidence (majority support) of the legislature. In addition, party discipline is enforced by party rules that give the leader of the party the authority to discipline members who don’t follow government policy. Members can be removed from the caucus, meaning they need to sit as an independent, and the party leader also signs nomination paper when candidates run for office. These rules create powerful incentives for members of the legislature to vote how their party leader tells them to. Finally, cabinet positions are prestigious and higher-paying, so members of the caucus have additional incentives to seek the approval of the party leader who gets to select cabinet ministers if their party forms the government.

This combination of system incentives and party rules means that in Canada, governments are very centred around the prime minster (at the federal level) and premiers (at the provincial level). Legislatures must pass budgets and other legislation in order for the government to operate, but in practice, policies are proposed by the executive and other members of the government caucus vote according to the directions they are given. However, the power of the prime minister (or premier) is not unlimited. If the government caucus perceives that the policies of the government, or other actions of the leader, are jeopardizing the electoral viability of the party, they can threaten to withhold their support for the party’s positions. If a prime minister or premier can’t hold confidence of his party in the legislature, he or she is likely to resign, as Premier Gordon Campbell did in British Columbia in 2011.

The dominance of the executive over the legislature is limited in periods of minority government. In that case, the governing party needs to get the cooperation from members of other parties to maintain the confidence of the legislature. In the case of majority government, the power of opposition parties is limited to the threat of exposure through Question Period, an opportunity for the opposition parties to formally question the actions of the government when the legislature is in session.

Voting

Members of the legislature are selected in elections, in an electoral system known as single-member, first past the post. Jurisdictions are divided into electoral districts (different for federal and provincial elections), also known as ridings, and the candidate with the most votes (not necessarily a majority) becomes the member of the legislature from that district. Provincially, the UBC Vancouver campus is in the Vancouver-Point Grey riding, represented by NDP MLA David Eby. Federally, UBC is in the Vancouver-Quadra riding, represented by Liberal MP Joyce Murray. There is no direct election for the Prime Minister or Premier. They are the leaders of the party that forms the government after the election, and they must run for election in a riding like other party members. Prime Minister Stephen Harper, for example, is the MP for Calgary-Southwest, and is Prime Minister because the party that he leads won a majority of seats in the 2011 election.

One important measure of a political system’s representativeness is how well votes get translated into seats in legislatures. Our electoral system works well in doing so when there are only two dominant parties. However, when three or more parties get significant vote shares, the potential increases significantly for distortions between the proportion of votes in the election and the proportion of seats in the legislature. Such has been the case in Canada in recent decades. For political scientists, Canada is an electoral curiosity. Duvenger’s law states that when you have single member districts and a plurality voting rule like we do, you are likely to have a two-party system. The last time a party received a majority of votes in a Canadian federal election was in 1984, and even then Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative Party just barely exceeded the threshold with 50.03% of the votes. In British Columbia, since 1972, the only election when a winning party won a majority was Gordon Campbell’s BC Liberal Party in 2001.

Minority-based majorities are not the only challenge when more than two parties are competitive in our type of system. You can also have situations when the party who wins the most votes doesn’t win the most seats. In the 1996 BC election, Glen Clark’s NDP won a majority of seats even though the NDP received fewer votes than Campbell’s Liberals (the Liberals won 41.8%, the NDP 39.5%). These types of misfires are more likely happen when there are significant differences in winning margins for the parties across ridings.

These distortions between seat and votes have increased calls for electoral reform in Canada. Demands for change have increased since 2011, when Stephen Harper’s Conservative Party of Canada won a majority in the House of Commons with only 39.6% of the vote. Harper’s party forms the conservative end of the political spectrum, meaning that more than 60% of Canadian voters that year supported parties less conservative than Harper’s. The main alternative to the Canadian system is proportional representation, which is designed to ensure that seats in the legislature closely match the proportion of votes parties receive in the election. In the 2015 Canadian election, the NDP, Liberals, and Greens all formally committed to pursuing electoral reform if elected.

The Production of Policies through Formal Processes

Production of policies at the provincial level

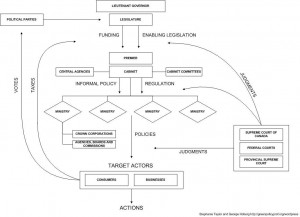

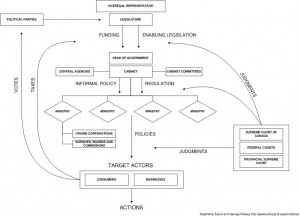

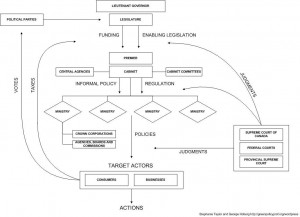

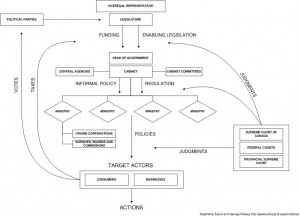

The accompanying figures illustrate how the various formal elements of the process combine together to form a system for the production of policies. The first diagram is for Canadian provincial governments, whereas the second generalizes for both levels of Canadian government. Public policies are authorized by enabling legislation and funded by annual budgets enacted by the legislature. The executive (cabinet and PM/premier) direct the implementation of these policies, either by passing regulations (delegated legislation) or other forms of policy, through ministries (government departments). These ministries consist of public servants (bureaucrats) who work under the supervision of a cabinet minister representing the government of the day. Implementation of these policies is designed to influence the behaviour of target actors such as business or consumers.

For example, the BC Forest Practices and Range Act (FRPA) is an act of the BC Legislative

Formal process for the production of policy in Canada

Assembly. The Forest Planning and Practices Regulation was passed by cabinet under the authority of FRPA. FRPA is implemented by the Ministry of Forest, Lands, and Natural Resources Operations, under the supervision (as of 2015) of Minister Steve Thomson. FRPA is designed to influence the behaviour of forest companies to ensure that forest management was carried out in a way that promotes a series of values built into the law, such as timber production and biodiversity.

The system also provides for feedback and checks. Business and consumers are taxed, and the revenues from those taxes flow into government treasuries to support government services. Periodically, citizens have the opportunity to vote to keep the government in power, or if they are not satisfied with the performance of the current government, replace the government with another political party.

The judicial branch also checks the actions of government. Courts can challenge Act of the legislature as inconsistent with the Constitution, and regulations or other actions of governments as inconsistent with the authority established in enabling legislation.

Additional Resources:

For a far more entertaining version, see Rick Mercer’s take on the RMR in 2009.